Essential Developer Principles #1–Divide and Conquer

With this post I am starting a new series in which I intend to cover a miscellany of developer ‘principles’. They are in no particular order, and I’m not promising any great regularity but I am intending to use some of the material I present here as part of the developer training where I work, so please feel free to suggest improvements or offer counterpoints.

The essence of software development is divide and conquer. You take a large problem, and break it into smaller pieces. Each of those smaller problems is broken into further pieces until you finally get down to something you can actually solve with lines of code.

If you can’t break problems down into constituent parts, you don’t have what it takes to be a programmer. Apparently some who purport to be developers can’t even solve trivial problems like FizzBuzz. They can’t see that to solve FizzBuzz (the “big” problem), all they need to do is solve a few much simpler problems (count from 1 to 100, see if a number is divisible by three, see if a number is divisible by 5, print a message). Once you have done that, the pieces aren’t too hard to put together into a solution to the big problem.

Cutting the Cake

But being a good developer is not just about being able to decompose problems. If you need to cut a square birthday cake into four equal pieces there are several ways of doing it. You could cut it into four squares, four triangles, or four rectangles, to name just a few of the options. Which is best? Well that depends on whether there are chocolate buttons on top of the cake. You’d better make sure everyone gets an equal share of those too or there will be trouble.

A good developer doesn’t just see that a problem can be broken down; they see several ways to break it down and select the most appropriate.

For example, you can slice your ASP.NET application up by every web page having all its logic and database access in the code behind – vertical slices if you like. Or you can slice it up in a different way and have your presentation, your business logic, and your database access as horizontal slices. Both are ways of taking a big problem and cutting it into smaller pieces. Hopefully I don’t need to tell you which of those is a better choice.

Keep Cutting

Alongside the mistake of cutting a problem up in the wrong way likes the equally dangerous mistake of failing to cut the problem up small enough.

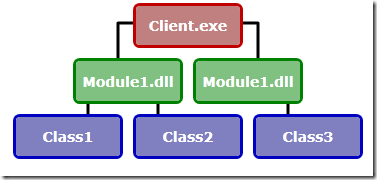

In the world of .NET you might decide that for a particular problem you need two applications – a client and a server. Then you decide that the client needs two assemblies, or DLLs. And inside each of those modules you create a couple of classes.

All this is well and good, but it means that your tree of hierarchy has only got three levels. As your implementation progresses, something has to receive all the new code you will write. Unless you are willing to break the problem up further, what will happen is that those classes on the third level will grow to contain hundreds of long and complicated methods. In other words, our classes bloat:

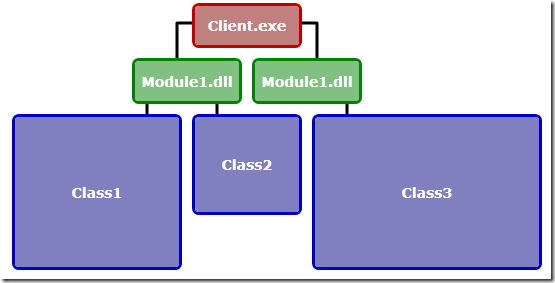

It doesn’t need to be this way. We can almost always divide the problem that a class solves into two or more smaller, more focussed problems. Understanding the divide and conquer principle means we keep breaking the problem down until we have classes that adhere to the “single responsibility principle” – they do just one thing. These classes will be made up of a small number of short methods. Essentially, we add extra levels to our hierarchy, each one breaking the problem down smaller until we reach an appropriately simple, understandable, and testable chunk:

I’ve not shown it on my diagram, but an important side benefit is that a lot of the small components we create when we break our problems up like this turn out to be reusable. We’ve actually made some of the other problems in our application easier to solve, by virtue of breaking things down to an appropriate level of granularity. There are more classes, but less code.

And that’s it. Divide and conquer is all it takes to be a programmer. But to be a great programmer, you need to know where to cut, and to keep on cutting until you’ve got everything into bite-sized chunks.

A place for me to share what I'm learning: Azure, .NET, Docker, audio, microservices, and more...

A place for me to share what I'm learning: Azure, .NET, Docker, audio, microservices, and more...