Push Complexity to the Edges

I blogged a while back about “technical debt interest rates” where I argued that not all “technical debt” is created equal (and by technical debt, I am meaning code that is hard to maintain, e.g because it is overly complex or tightly coupled). Sometimes shortcuts make you pay in the long run, but other times they turn out to be a smart move after all. This raises the question of whether you can know how risky the technical debt you are introducing actually is.

Of course, without the ability to accurately predict the future, you can never know, but I want to propose a simple rule of thumb. The closer your compromised code is to the core of your codebase, the greater penalties it will incur.

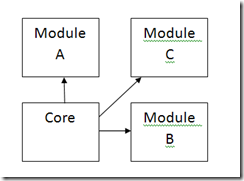

Imagine an application whose architecture looks like this:

Here we have a fairly clean architecture where the core part of the application talks to three modules which are all isolated from each other. Suppose for a minute that Module A contains terribly complicated code because it was rushed out the door in a hurry. The technical debt it contains won’t actually cause us any pain at all if we need to extend Module B or Module C, or even add a new Module D. That is because it is isolated from the rest of the application.

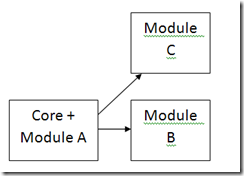

However, consider a more realistic version of what happens when technical debt is introduced:

Here, the code for feature A was not isolated into its own module, but is inextricably intertwined with the core code. Now we are in big trouble. Because although we may not want to make any changes to feature A, anyone who works on the core of our application has to deal with the added complexity that is in there.

If this seems obvious, that’s because it is. After all, the very compromise being made when introducing technical debt is often that we don’t have time to separate the new functionality out into its own isolated module. However, the time required to extract feature A out afterwards is much greater than doing it right first time, and becomes almost impossible after the same mistake has been made several times over.

The key is to recognise when you are introducing complexity into the core of your application. This is technical debt that will be very expensive. A plugin-in architecture, on the other hand, can allow you to have several isolated areas of complexity that may not require the debt to be paid back. This is why it makes sense to start new applications with a loosely coupled, extensible architecture, rather than deciding you will plumb one in at a later date.

A place for me to share what I'm learning: Azure, .NET, Docker, audio, microservices, and more...

A place for me to share what I'm learning: Azure, .NET, Docker, audio, microservices, and more...